Kyiv 2014

My trip to a post-revolutionary Ukraine

March 12 (Wednesday taking off)

In the morning, against my better judgment, I used public transportation to go to Kyiv's secondary airport, Zhuliany. The Metro leg of the trip was followed by a confusing walk past several bus stops, through vendor kiosk areas, and around corners, in order to catch a marshrutky, which promptly stopped in rush-hour traffic. After crawling to the airport stop, the terminal remained a few minutes' walk down the road and off to the side. Walking from street to the airport — with only 10 minutes to spare, mind you — was not my usual airport experience. However, after I entered the terminal, the remainder of the experience wasn't too unfamiliar, though I was a bit surprised that the flight wasn't as packed as the others I'd taken.

Still, I did make it safely out of Ukraine, without any significant problems. The border agent, as with many folks I saw around Kyiv, especially the Maidan, sported camouflage. Up close, I could see that the border agent's — the soldier's — blood type printed on his uniform. Although Ukraine may have soldiers at its borders, it nonetheless has rather porous borders, in the sense that Russians can enter, exit, and work with minimal fuss. This has been convenient for Mila — who has a Russian passport — but it means that surprises like the one in Crimea are easier to spring on Ukraine than they would be, say, on the U.S.

Crimea would, in the following days, declare itself independent, then be annexed by Russia. This adds to Russia's collection of frozen conflict zones under its influence. There is Crimea to the south and the aforementioned Transnistria to the west. To the north of Ukraine is Russia's tightest ally, authoritarian Belarus, and to the east is Russia itself, so Ukraine now has Russia at all four directions, I'm afraid. (Nonetheless, there are also small border segments shared with friendlier counties: Poland, Moldova, Hungary, and Slovakia.) But Ukraine and Belarus aren't the only countries Russia regards as in its sphere of influence. In 2008, Russia invaded Georgia, cementing the Russia-sponsored conflict zones and breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which made up about 15% of Georgia. And, since around the time of the break-up of the Soviet Union, Russia has involved itself in the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Though the Soviets historically favored Azerbaijan, giving it some territory with Armenian majorities, the Russian Federation has promoted the status quo, in which both that and other regions are controlled by Armenia, taking away, again, about 15% of the other country. This switch allowed the conflict to remain frozen, dragging down both countries politically and economically. So Crimea is part of a long line of Russian sabotage which long predates even Putin.

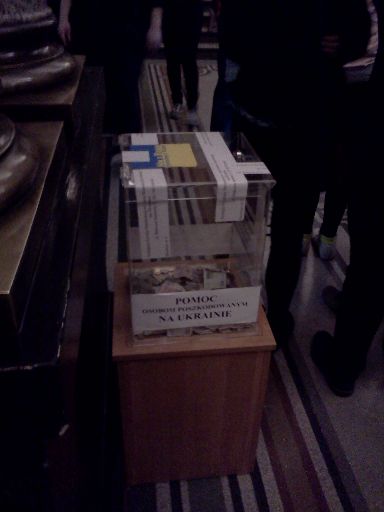

While in Poland, I would see a bit of anti-Ukrainian sentiment in museums examining the WWII period. Many Ukrainians fought on the Nazi side and even more fought on the Soviet side, so Poland saw Ukrainians in uniform going both ways. However, now that Ukraine seems to be looking toward the West, and struggling, the sympathy clearly lies with Ukraine. I saw three boxes in prominent places, such as national museums, marked for giving aid to Ukraine, usually the Maidan in particular. Inside a Ukrainian Orthodox church in Wrocław, the one with the Maidan memorial, I saw both a contribution box and reports from Maidan. There was also another Holodomor exhibit and memorial.

|

One of the most interesting responses to the crisis I heard was while touring the cathedral in Wawal Castle in Krakow, a traditional burial place for the great figures in Polish history. Two of those buried there are Polish president Lech Kaczyński and his wife Maria. They were killed, along with many high officials, in a 2010 plane crash in Russia. Ironically, they were on their way to Warsaw to attend an event commemorating the 70th anniversary of the Katyn massacre, the 1939 murder of 22,000 Poles, many prominent, in order to pacify the eastern part of Poland that the Soviets had just invaded. The massacre had taken place near where the plane took off, which is why they were there.

Given the number of mysterious deaths and poisonings of Putin opponents outside of Russia, many wondered whether the accident was not so accidental after all. An investigation found that pilot error was to blame, but the English-language tour guide of the crypt clearly thought otherwise, that this was an attempt to keep down a Russian neighbor, much like the invasion of Georgia and Ukraine, the perpetuation of frozen conflicts, the poisoning of Viktor Yushchenko, or the 2007 cyberattack on Estonia. After all, if Putin feels that he has the right to invade anywhere he doesn't like that has a Russian majority, there are many parts of the world which wouldn't be safe (including, theoretically, parts of the U.S.).

I'd hesitate at laying a plane crash at his feet with no evidence to support this, but the years that followed showed just how far Putin was willing to go for power and control. You can say one thing for Putin: He certainly made my trip to Kyiv interesting.

start // back / next