Kopek, denga, polushka: An English-language guide to Russian wire money

|

Introduction

Russian wire money, hand-struck between the 1360s and 1710s, is a fascinating part of the rich history of pre-Imperial Russia. There are numerous varieties of these coins, some of which are available for a few dollars, and others of which are unavailable at any price, having only one known specimen.

Unfortunately, it can be hard to find English-language resources about these coins and hard to use Russian-language resources. It doesn't help that the denominations that originally referred to these coins eventually referred to their copper replacements, or that there are just too many varieties to be included in guides to world coinage. Just developing a basic understanding of the coins can be a chore. However, by assembling the most useful resources in one place, I hope this page makes it easy for English-speaking collectors to begin collecting these coins.

A brief history of Russian wire money

|

The Bank of Russia Museum describes a two-century stretch from the 12th to the 14th century as a "coinless period."† During this time, due to larger regional changes in trading patterns, the various Eastern Slavic lands went from being places in which (mostly foreign) coins helped facilitate trade to ones in which coins were rarely used. In their place were tools of barter like beads, spindles, or furs. Large monetary exchanges were made using precious metal bars, known as grivna. Silver grivna weights were eventually standardized within each principality. Kyivian ones were smaller than the ones from the Novgorod Republic, which were about 200 grams, the exchange equivalent of around 500 squirrel pelts. A modified version of the word "grivna" is, today, the unit of currency in Ukraine, the hryvnia.

|

The Tatar Mongols of the Golden Horde would eventually reintroduce the concept of coinage to the lands they conquered in the 13th century. The Golden Horde minted coins by taking silver wire, cutting it, and hammering it flat. In the early 1360s, the conquered Europeans imitated this practice using Mongol designs. In the late 1370s, The Principality of Moscow, under Dmitry of the Don, started to use its own designs, with neighbors following suit. The wire was measured out in fractions of grivna, so coin weights were standardized by principality. Even when, in the late 15th century, Dmitry's great-grandson, Ivan III, ended Moscow's status as Mongol tributary and united the Russian lands into a single country, different places continued using different designs and different weights.

Ivan III's grandson, Ivan IV, inherited Moscow's throne in 1533 at age three. Almost immediately, his mother and regent, Elena Glinskaya, reformed Russian currency. Coins weighing 0.68 grams, close in weight to the 0.78-gram coins minted in (Veliky) Novgorod, were called "kopeks." Almost all of these had text on one side and a horse and rider with a spear pointed toward the lower right on the other. Since "spear" is similar to "kopek" in Russian, it's often stated that that's how the coin was named, but that etymology is disputed. It might have been named after a Central Asian Mongol khan or after a Russian word for saving money.

|

A half-kopek, closer to the weight of the standard coin of Moscow, was called a "denga," the plural of which, "dengi," remains to this day the Russian word for "money." It has a similar design but with the rider holding a saber. A quarter-kopek, tiny and far less common, was a polushka, with a bird in place of the horse and rider.

|

The denga was ubiquitous during the reign of Ivan IV, later known as Ivan the Terrible, but in later years the kopek was more common. During the 1598-1613 succession crisis known as the Time of Troubles, kopek weights varied greatly due to fiscal and political concerns, starting the 15-year period at 0.64 grams and ending it at a mere 0.49. The crisis ended after the Second People's Militia set up a provisional government in Yaroslavl and eventually retook Moscow from the occupying Poles. The 2013 unveiling of a Yaroslavl memorial in the form of a giant Yaroslavl 1612 kopek (video here), indicates the kopek's significance in this history: Goods and labor supporting the uprising were paid for with these coins, identical in weight to those of the occupying Poles. Such coins are now among the rarer of varieties. The specifically depicted kopek, having catalog (KG) number 304, bears the name of the last ruler before the Time of Troubles, who died over 14 years before its production. In early 1613, his name was replaced with that of Tsar Michael, the first of the Romanov Tsars.

Half a century after the Time of Troubles, Michael's son, Tsar Alexis, replaced the silver coins, by then down to 0.46 grams, with copper ones. This led to rapid inflation, counterfeiting, and, after eight years of copper, the Copper Riot, a violently crushed uprising.

|

As a result, wire coins were once again struck from silver. Alexis' son, Peter I – Peter the Great – further shrank silver kopeks from 0.39 grams to 0.28, then gradually phased them out all together, ending production in 1717. The phrase-out period of almost two decades saved Peter from having to face another coin-related uprising. Due to the small weight, these later kopeks take up only a fraction of the surface area of the die used to make them. On some, all you can make out is, "Pyotr," even when the corresponding die reads "Tsar and Grand Prince Pyotr Alexeyevich of all Russia." The below kopek lacks the rider's crown, the horse's head, and the date (1702). More on this below.

|

|

Kopeks remained a unit of currency throughout Russian history, albeit redenominated multiple times in the 20th century. An explanatory side note: "Devaluation" is making money worth less, "debasement" is doing so by reducing precious metal content, and "redenomination" is replacing one valuation system with another. For example, Russia's currency today, the second Russian ruble, is worth 1,000 first Russian rubles. The second ruble's corresponding kopek has an updated version of the rider with spear.

|

This design was used for all coins worth less than one ruble from 1997 until the end of minting of such coins in 2015. Its familiar design, no doubt chosen due to its similarity to that of the silver kopek, was, in fact, based on a 15th century painting. The retirement of the design was due to another crisis-driven devaluation, this crisis being the Russian financial crisis of 2014, which relates to the subject of this site's homepage.

The Russian Federation's kopek is, as of late 2024, worth about 1/100 of an American cent, even though – using redenomination as a guide – it is equivalent to 100,000,000,000 century-old kopeks from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). This equals a modern devaluation rate of around 30% per year; in post-Soviet times, devaluation has averaged even higher, in the high 30s. By contrast, debasement from Ivan IV to Peter the Great averaged only about 0.5% per year, yet was still evident due to the shrinking size of the kopek.

Digression: The "coinless period"

|

† For those wanting to learn more, this page has information about the creation of the aforementioned Bank of Russian virtual museum, while this 1986 Harvard University article has information about the economy of the pre-Mongol "coinless period."

There is much uncertainty over:

- how "coinless" the period was,

- how commonly coinage was used prior,

- what replaced coins (mainly furs? mainly spindles? different items during different parts of the time period?),

- the duration of the period (around 1140-1350?),

- its cause(s) (Northern crusades? debasement of Central European coinage? disruption of trade with the Islamic world? reduced use of silver in the Islamic world? divisions among local principalities?).

Assertions and interpretations regarding these are often politicized: Linked here is a (Russian-language) claim that the designation of a "coinless period" is an anti-Russian "conspiracy in historical science" intended to make "ancient Russia" seem backward and powerless. Others claim that the common explanation of the period as being caused by internal fragmentation and isolation is a pro-Russian myth furthering the idea that external forces can never bring down a "Russian" state, only internal ones. Some people even claim that wire coins in Slavic lands predated the Tatar Mongols rather than being introduced by them. Even if true, however, it was the Tatar Mongols who popularized them — and the use of such coins over other items of trade.

Identification

|

Identifying a coin, especially from just part of its design, is part of the challenge of collecting these coins. Since most literature is unavailable in the Anglophone world and most websites are in Russian, it's hard to figure out how to do so if you don't know where to look. In addition, non-Russian speakers will need a translator like that in Chrome or Safari, and a guide to the Russian alphabet like Wikipedia. I advise the use of these Russian- and English-language resources:

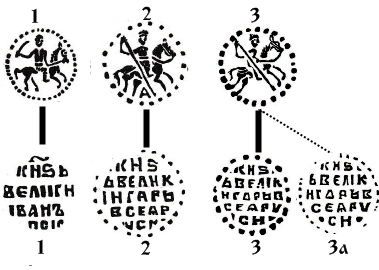

- The website http://www.learn-your-history.in.ua is that of a Ukrainian coin dealer who, unfortunately, does not ship internationally. However, collectors outside of Ukraine can take advantage of the site's identification charts (archived here) in order to identify ruler, obverse, and reverse. These charts cover years 1533 to 1704, and thus most, but not all, Russian wire coins. A portion of one chart is shown above. They are separated by ruler, mint, and denomination. Coin text and weight are the best way to determine these; just be aware that wear and clipping mean that specimens often weigh significantly less than when originally minted.

- Either way, the next stop is Russian coin, which I've mirrored here due to certificate problems with the original. The site covers 1420 to 1717, and is essential for determining the catalog number of your coin. Its illustrations of the coins' designs will also help you to distinguish what's on your coin more clearly. Be forewarned, however, that, although its catalog numbers are correct, some of the numbers identifying designs on each side of coins may differ from other sources. You may needed to go by picture rather than number.

- Dzmitry Hulecki's 48-page English-language Russian Wire Coins 1533-1645 is a useful book on the subject, with information on dates, weights, pricing, example pieces, and historical background. However, it is an optional reference, neither necessary nor sufficient for full identification. That's fortunate, since searches on eBay, Amazon, and a worldwide library database only yield one copy — at a limited-access Stanford library storage facility. As such, I've linked its most useful page, a weight-related chart, here. (The chart doesn't include the solo reign of Peter the Great, during which kopek weight was reduced to 0.28 grams.)

| . | 1400s | . | 1500s | . | 1600s | . | 1700s | . | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| < Mongol period | Russian Tsardom | Empire > | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ivan III | Ivan IV | Peter I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1533 → | Identification charts (Russian) | ← 1704 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 1420 → | Russian coin (Russian) |

← 1717 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 1533 → | Russian Wire Coins (English) | ← 1645 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ↓ | 1533 → | Catalog of Medieval Coins of Russia (bilingual) | ← 1717 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dates and mintmarks

|

While some wire coins have dates corresponding to the putative years of mintage, not all do. Those that don't will correspond to either a specific year or range of years. Those that do will have their dates written using Cyrillic numerals, which represent the Byzantine year for coins prior to 1700 and the Julian year for coins after. This calendar reform was one of Peter the Great's earliest reforms.

Dates, when present, are below the horse, and useful in expediting coin identification, especially for those of Peter the Great, only some of which are covered by the aforementioned identification charts. Mintmarks indicating the city of minting, when present, are also below the horse, the mintmark before the date when both are present. As in the above example of the "smaller kopek of Peter the Great," however, often a die with a date strikes a coin in a way such that the date itself is missing.

Dates first appeared on Novgorod-minted coins in 1596 (Byzantine year 7104) and were present in them for years. This was due to a monetary reform that came after the increased trade resulting from the end of the 1590-1595 war with Sweden. Outside of Novgorod during this period, the only dated coins were from Pskov in 1599, and even some of those with Pskov mintmarks were actually made in Novgorod. When the 1610-1617 Ingrian War saw Sweden conquering Novgorod in 1611, it was only the Swedes overseeing dated "Russian" coinage. They did not retain accurate years of mintage, as noted in the chart below. Thus Byzantine year 7118 (1610) was the last date on Novgorod wire coins.

After the Swedish occupation of Novgorod ended in 1617, one Novgorod-minted design continued to have an incorrect date (1610) for nearly a decade, minted alongside dateless coins. Thus wire coins have no dates between Byzantine years 7118 and 7204 (1610 and 1696).

Starting with the inception of Peter the Great's solo reign in 1696, all coins – more accurately, all dies – had dates on them. Dates are often not the full numerical date; the millennium can be implied. Even when its value is expressed, the thousands symbol "҂" may be present, absent, or combined with the first numeral. Also, since Byzantine and Julian years do not perfectly align with Western (Gregorian) years, everyone just uses the nearest approximation, e.g., 1596 for the Byzantine year that began in September 1595. During the time of Peter the Great, coins minted at the Kadashevsky Mint (1701-1737, located in Kadashevskaya Sloboda, across the Moskva River from the Kremlin) had the millennium indicator ("а"), while coins minted at the Old Mint (possibly 1535-1717, near St. Basil's Cathedral‡) only sometimes did (as "Я" or "А").

Date marks

Below is a table mapping Cyrillic dates to Gregorian years; some dates do not correspond to exact year of coinage due to the chaos of the Time of Troubles.

| Cyrillic number | Corresponding year | Gregorian year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| РД | 7104 | 1596 | "НОРД" with Novgorod mintmark |

| РЕ | 7105 | 1597 | "НОРЕ" with Novgorod mintmark |

| РЅ | 7106 | 1598 | "НОРЅ" or "ПРЅ" with mintmark |

| РЗ | 7107 | 1599 | "НОРЗ" or "ПСРЗ" with mintmark |

| РИ | 7108 | 1600 | "НОІРИ" with Novgorod mintmark |

| РѲ | 7109 | 1601 | "НОРѲ" with Novgorod mintmark |

| РІ | 7110 | 1602 | "НОРІ" with Novgorod mintmark |

| РАІ | 7111 | 1603 | "НОРАІ" or "НРАІ" with Novgorod mintmark |

| РВІ | 7112 | 1604 | mintmark "Н" above date |

| РГІ | 7113 | 1605 | "НРГІ" with Novgorod mintmark; Swedes also used this date 1616-1617 |

| РДІ | 7114 | 1606 | mintmark "Н" above date |

| РЕІ | 7115 | 1607 | printed as "Н" above "РϜІ" |

| РЅІ | 7116 | 1608 | mintmark "Н" above date |

| None | None | various | "НРД" is not a date, but a mintmark for Novgorod, used in 1609 and 1611 |

| РИІ | 7118 | 1610 | printed as "РІН"; Swedes also used "РІН" 1611-1615, as did one design from Novgorod 1618-1627 (KG#647) |

| СД | 7204 | 1696 | has "Г." suffix for "year" |

| СЕ | 7205 | 1697 | |

| СЅ | 7206 | 1698 | |

| СЗ | 7207 | 1699 | |

| СИ | 7208 | 1700 | |

| ЯΨ | 1700 | 1700 | "Я" can be "А" |

| ЯΨЯ | 1701 | 1701 | "Я" can be "А," "а" for Kadashevsky Mint |

| ЯΨВ | 1702 | 1702 | "Я" can be "А," "а" for Kadashevsky Mint |

| ЯΨГ | 1703 | 1703 | "Я" can be "А," "а" for Kadashevsky Mint |

| ЯΨД | 1704 | 1704 | "Я" is "а" for Kadashevsky Mint |

| аΨЕ | 1705 | 1705 | only minted at Kadashevsky |

| ЯΨЅ | 1706 | 1706 | "Я" is "а" for Kadashevsky Mint |

| аΨЗ | 1707 | 1707 | only minted at Kadashevsky |

| аΨИ | 1708 | 1708 | only minted at Kadashevsky |

| ЯΨѲ | 1709 | 1709 | "Я" is "а" for Kadashevsky Mint |

| ЯΨІ | 1710 | 1710 | "Я" is "а" for Kadashevsky Mint |

| ΨЯІ | 1711 | 1711 | preceded by "а" for Kadashevsky Mint |

| ΨВІ | 1712 | 1712 | only minted at the Old Mint |

| аΨГІ | 1713 | 1713 | only minted at Kadashevsky |

| ΨДІ | 1714 | 1714 | only minted at the Old Mint |

| ΨЕІ | 1715 | 1715 | only minted at the Old Mint |

| ΨЅІ | 1716 | 1716 | preceded by "а" for Kadashevsky Mint |

| ΨЗІ | 1717 | 1717 | "аΨІЗ" for Kadashevsky Mint |

Digression: Mint locations

|

‡ What Google Maps refers to as the "Old Mint" is actually the newer "Red Mint," which, like the Kadashevsky Mint, opened later than the older Old Mint, during the time of Peter the Great. Google Translate calls the newer mint "Chinese," but that's due to its location, Kitay-gorod, the center-most area of Moscow; "kitay" is the modern Russian word for "China", although its meaning in the context of "Kitay-gorod" is unclear, much like the origin of the word "kopek" itself.

The exact location of older mints (KML, e.g., for Google Earth) outside of Moscow, if indeed they had static locations, appears lost to history, or at the very least obscure. Even the exact location of Moscow's Old Mint seems unclear; Russian-language Wikipedia, which specifies exact locations for other Moscow mints, only says it is was on Ulitsa Varvarka, a short street starting at the famed St. Basil's Cathedral. Also, although Russian-language Wikipedia states that the Old Mint closed down in the 17th century, Kleshchinov and Grishin state that kopeks dated up through 1717 ("ΨЗІ") are from this mint.

Before Peter's time, there were also two short-lived mints that primarily minted the copper wire kopeks that replaced silver from 1655 to 1663. The New Moscow English Mint – or just "New Mint" – was located just steps outside of Kitay-gorod in the Basmanny District. Opened in 1654, it was designed to mint round coins, but a lack of skilled workers meant that, starting from 1655, it only minted copper wire coins, ceasing operations upon the 1663 return to silver. The eponymous English, the property's original inhabitants, had been kicked out of Moscow in 1649 due to the execution of King Charles I.

In addition to this New Mint, the Old Mint, the Pskov mint, and the Novgorod mint, copper wire coins were also briefly minted in Kukeinos mint. Now called Koknese, Latvia, in 1656 Kukeinos was a Swedish fortress captured by Russia, minting copper wire coins from 1659 until its return to Sweden in 1661.

Russian coins were also minted in Tver from the time of its seizure in 1485 to well into the reign of Ivan IV. Coins in the Russian style were also minted outside of Russia by neighbors like Denmark and Sweden. Considered "counterfeit," these are also collectable and relatively rare.

Other identifying characteristics

|

Dates and/or mintmarks, if present, are the most reliable way to narrow the range of possible matches. Another is weight, although the manual fabrication and fragility of the coin to wear or fracture means that this is only somewhat helpful. The obverse, the side with the horse, could narrow things down as well, but although it's generally easier to use the text on the reverse. This may include the ruler name and/or title, or, failing that, at least distinguishing text style and placement.

Purchase

|

I've never seen a wire coin in an American coin show or coin shop, so your best bet is looking online, generally on eBay. The market for these coins, as you can imagine, is the largest in the lands through which they once circulated. For example, take Ukrainian interest: The Cossack Hetmanate, based in the heart of modern-day Ukraine, pledged allegiance to Moscow in early 1654 during an anti-Polish rebellion. This led to war between Russia and Poland, funds for which were raised by the issuance of copper wire kopeks. These copper pieces were issued from 1654 until the Copper Riot brought back silver.

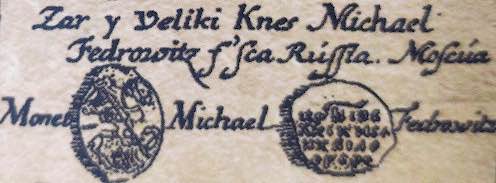

When shopping online, be aware that different listings may use completely different words and phrases to refer to the coins: "Moscow," "Russia," "wire," "silver," "kopek," "denga." Trying various combinations may be necessary to find what you want. If the coin being sold is fully identified, that will save the need for going through the identification process. A starting collector wanting to go through this process, however, might want to look for lots of several coins. Check photos to be sure you're getting the variety you expect, though; one lot I obtained, shown at the top of this page, turned out to all be from one Tsar (Michael).

Other resources

The standard guide for wire coins from Ivan the Terrible to Peter the Great is Kleshchinov and Grishin's four-volume Catalog of Medieval Coins of Russia. Its "KG" catalog numbers are most the widely used system for denoting coin varieties, and, unlike most online resources, it includes the wire coins of the copper period (1655 to 1663). Its books have some readable English text along with their native Russian, but each book can be expensive and hard to find. The dealer at http://www.learn-your-history.in.ua sells inexpensive reprints if you have a Ukrainian address to ship to; pirated electronic versions exist as well. But the above online resources should be sufficient.

(Regarding the guide's title, "Medieval" is a relative term here, a legacy of the Soviet adoption of the French "long Middle Ages" theory. This theory held that, due to its greater impact on the people, the Enlightenment, not the Renaissance, ended the Middle Ages.)

NOTE: I am including flags indicating the national origin of the online material below, just in case one country or another has connection problems related to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Remember that there's always archive.org.

🇬🇧 English-language websites 🇬🇧

- A bit of information about a kopek of Peter the Great (🇺🇸/🇨🇦), especially the text side

- Various other examples (🇺🇸), with some history

- Hundreds of other examples (🇺🇸) of these and other Russian coins

- Information about a Russian-language numismatic periodical (🇷🇺) (in English)

- A certificate of information (🇺🇸) provided by one seller with kopeks of Peter the Great

- A Ukrainian's blog entry about finding wire coins using a metal detector (🇺🇦); the corresponding Reddit post (🇺🇸) was the most popular of 2020 on r/AncientCoins (in spite of the time period)

🇷🇺 Russian-language websites 🇷🇺

- The aforementioned http://www.learn-your-history.in.ua (🇺🇦) site has identification guides and many other resources.

- The aforementioned Russian coin (🇺🇸) site is useful for identifying early coins and assigning catalog number to wire coins in general. Original here (🇷🇺). Mirror here (🇯🇵).

- The aforementioned periodical's final issue (🇷🇺) concentrated on wire coins.

- Wikipedia's Russian-language pages on (Russian) denominations of money (🇺🇸) have more information than the English-language versions.

- Russianchange (🇷🇺) has many articles regarding early Russian coinage as well.

- All Coins (🇷🇺) has many resources, including book excerpts.

🇷🇺 More Russian books 🇷🇺

The last resource above is the best one for books, since many are given as text and thus easily translatable. Readers capable of reading Russian may also appreciate the following:

- http://www.learn-your-history.in.ua (🇺🇦) includes a number of Russian-language books, though the most useful information in them is included in the identification guides, and the books' (Russian) text is on scanned pages served in JPG or DjVu archived in RARs. The above-linked book excerpts are thus more convenient, e.g., for Melnikova's 1989 historical account, available on both websites.

- A Russian site has 1843's A Description of Russian Coins and Medals (🇷🇺), a (non-comprehensive) catalog of coins and medals by ruler from 1425 to 1725. (Click on "PDF" and enter any email address to start download.) Its author was Friedrich von Schubert, son of Theodor von Schubert and grandfather to Sofya Kovalevskaya. Figures start on page 343.

- Google Books has 1834's A Description of Ancient Russian Coins (🇺🇸), where "ancient" is relative; most of these fall under the Late Middle Ages given Western definitions. The introduction discusses the difficulty of identifying oft-poorly struck coins from this underdocumented period of Russian history. Sections include: "Grand Duchy of Moscow," "Grand Duchy of Tver," "Grand Duchy of Ryazan," "Specific Princes," "Novgorod and Pskov," and "Uncertain." Figures start on page 241.

🇬🇧 English-language historical resources 🇬🇧

- Wikipedia's list of Russian monarchs (🇺🇸) is one launching point for learning about the rulers whose names grace the coins.

- The Romanovs. The History of the Russian Dynasty (🇺🇸/🇷🇺) is a Russian documentary about the Romanovs, made for the 2013 400th anniversary of their ascent to power. The link has the spoken track in English.

- The Rurik Dynasty (🇺🇸/🇷🇺) was made as a companion to The Romanovs, covering the prior major dynasty of Russia. The link has English subtitles.

|