Kyiv 2014

My trip to a post-revolutionary Ukraine

February (prologue from California)

On the first week of February 2014, I was laid off. A week later, I booked a ticket to Kyiv. A week after that, all hell broke loose: Nearly a hundred protesters were killed in Kyiv, triggering a sequence of events that led to President Yanukovych being removed from office and fleeing the country. The U.S. State Department issued a travel warning for not only Kyiv, but all of Ukraine. And at the end of the month, hours before my flight left, Russia invaded and occupied the Crimea, Ukraine's southernmost peninsula.

It was quite a month leading up to my departure. At the start of the month, with protests intensifying, I did ask Mila, whom I would visit in Kyiv, to think about having a plan in case it wasn't safe in the capital and leaving the country was difficult, especially in the week following the Olympics, the last week of the month. Russia would have a lot less to lose in cracking down on its neighbor after their Olympics had finished. That worst-case scenario didn't happen, but it certainly did get a lot worse than I'd expected. When the old government attempted to end the protests, she informed me that the subway was shut down and that the Kyiv-Lviv train was not running due to "corrosion" on the line. This was not something I wanted to hear, having initially planned on visiting Lviv as well. (The "corrosion" was most likely the influx of Westernized Lviv residents coming to Kyiv to protest.)

In any event, never have I followed the news so intently in my adult life, or so seriously rethought a trip. And it's not like I haven't had other opportunities to rethink. Between booking and leaving on a trip to Israel, the Second Intifada broke out. My two East Asia trips corresponded to two disease outbreaks (SARS-CoV-1 and H1N1). And I passed Gezi Park in Istanbul about an hour before protests there. Though no one was seriously hurt that particular day, travelers I met there did have to run into nearby businesses to avoid tear gas.

But Mila said Kyiv was safe, everything seemed safe, and Crimea was 500 miles south of Kyiv. So I packed my bags and — initially with more dread and less excitement than I would have desired — went to Kyiv.

(A word about that spelling: When the city was controlled by Russia, the romanization of the Russian-language name was "Kiev," as in "Chicken Kiev." "Kyiv," today's officially preferred spelling, is from the Ukrainian. English-speaking media have largely settled on the pronunciation "KEEV," no doubt because the Ukrainian pronunciation has a vowel sound unfamiliar to English speakers.)

March 1 (Saturday in the air)

I want to say from the outset that my views are those of someone who speaks very little Russian and no Ukrainian, one who really only spoke at length to two people in Kyiv, both American. It is easy to misread things when flying into a place for a week or two and talking to only a few people. Some so-called journalists seem to make careers of doing so. So take what you read here as just my views, not a complete truth.

I am not the first person in my family to visit Kyiv. During the Cold War, my parents visited Kyiv as part of a trip across the Soviet Union. Upon telling this to an American officer, my dad got the reply, "You picked a hell of a place to go for vacation!"

By late February 2014, folks were saying similar things to me. Some were alarmed by the prospect of my planned travels, while others didn't think of it as such a big deal. In either case, it's not often that a person finds himself landing at the precise place and time in which history itself is being made.

Not that I knew to expect that ahead of time. My reasons for traveling to Ukraine in March were more prosaic than that of watching history unfold first-hand. Mila and another Kyivan friend were planning to travel within Ukraine during the second week of March, and I planned to join them both during their travels and in Kyiv; that sounded far better than traveling alone. This plan ultimately got canceled due to circumstances beyond our control — mostly unrelated to the protests — and I only saw Kyiv (and only saw Mila). I had wanted to visit the former Soviet Union and had been taking a bit of Russian in preparation. The Russian Federation, however, seemed dicey for a last-minute trip, as American tourists have to get invitations to the country in order to get a visa. Plus, Kyiv is, as pro-Russian Ukrainians like to point out, the birthplace of Eastern Slavic culture, that which covers Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Moscow and St. Petersburg may be larger and more geared towards tourists, but Kyiv is where it all began.

The long flight from San Francisco to my connection in Amsterdam gave me the opportunity to practice the tiniest bit of Russian and Ukrainian, as well as to watch a few movies, one of which was 20 Feet from Stardom. This documentary about back-up singers would go on to win the full-length documentary Academy Award mere hours later, though of course that isn't why I mention it here. The reason it is pertinent to this trip is that I had seen it once before, during Mila's final days in the States. Back then, after the film was over, Mila told me that she was surprised to find that she actually knew one of the back-up singers profiled in the film. Claudia Lennear sang and danced with Tina Turner as an Ikette and became close friends with Mick Jagger and David Bowie after more singing gigs. However, she eventually switched careers, going back to school so that she could teach foreign languages, specifically French and Spanish. Mila, who always had an interest in foreign languages, met her there, and they actually talked quite a bit, in spite of their different backgrounds. Before the movie, though, Mila had had no idea about her past. And, back when she knew Claudia, Mila had no idea that she too would leave a promising career to teach a foreign language — in this case, English to Ukrainians. This would be my first time seeing her since she'd left.

March 2 (Sunday in Amsterdam)

My layover in Amsterdam was quite long, so I went into town, in spite of the direct train being down for the day. I spent most of my time there — including lunch — at the former synagogues that now comprised the Jewish Cultural Quarter complex of Jewish museums. Of those, I went to the Jewish Historical Museum, comprised of exhibits housed within the former Great Synagogue and New Synagogue, and the Portuguese Synagogue, full of detail regarding both its past and present functions. There's a lot of history there, and it's not unrelated to the continuation of my trip; both Amsterdam and Kyiv — as with many big cities in Europe — have a long history of a large Jewish population, wiped out by the Nazis, who loom large in the cities' histories.

Getting to the museums took me past the red light district, which I didn't realize until one of the women in the windows signaled for my attention. Though somewhat provocatively dressed, neither she nor her competition was showing much more skin than you'd see at an Academy Awards ceremony. I guess that's what some folks do in the morning. I chose that route — as well as those after the Jewish quarter — because it took me past the most museums, churches, and other tourist attractions I had missed my first time in the city five years prior, also a layover.

|

In addition to the Jewish quarter, I saw the Gassan Diamond museum, the flower market (complete with marijuana starter kits), and Jordaan, with its busy galleries and sports bars. I snacked on the go, excepting an actual lunch of a simple but delicious cheese sandwich at a Jewish museum café. As a vegetarian, I was glad to have a Kosher café, which had more options for me than your typical European restaurant. The meal came with pickles, which I usually don't like, but these were sweet, subtle, and tastier than their American counterparts. Considering the prevalence of pickled food in Eastern Europe, this was a good sign. That was lunch; so as not to be late for my flight to Kyiv, I just grabbed some fries for "dinner." This was good, since there was no vegetarian meal option on the flight, just cake. Marie Antoinette eat your heart out.

|

|

|

|

Another treat I'd get on the flight itself was a "stroopwafel," a thin, caramel-filled cookie that seemed to have become quite popular in Amsterdam in the years since I was last there; I picked up a package of them for Mila. When I'd give them to her upon my arrival in Kyiv, she'd say that she loved them, but that they were also available there. I later heard of a San Francisco startup dedicated to these treats. Thus it is with globalization.

At the gate to my flight, a man heard me speaking English and struck up a conversation, though it was closer to a monologue, similar to those introductions in the film The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, and with similarly dark subtext. He was going to Kyiv, hoping to single-handedly resolve the situation between Ukraine and Russia in three weeks. He noted that he had picked up an MP3 player in Germany — "possibly left by our friends to the east" — which he offered to me for the Russian lessons he had put on there. Had the device not been so tiny, I would have been a little scared — and he might have gotten a visit from airport security for taking an foreign item on the plane. When I pointed out that it wasn't right to take a mysterious item like that, he replied that he didn't always do the right thing. Great. When I tried engaging him in more conventional conversation, asking him where he was from and where (if?) he worked, he didn't want to specify, not even the country, not even the hemisphere. The folks you meet when you travel.

Fortunately, on the plane itself, the fellow I was seated near was a bit more sedate. He was from Kharkiv — the big city in the east often reported as being pretty much Russian. But his family was totally bilingual, talking equally in both languages (though his grandparents only spoke Ukrainian). I asked him some language-related questions before arriving and ending my long day falling asleep in Kyiv. Earlier in the day, I had been at Amsterdam's central Dam, but soon I'd be in Kyiv's now-world-famous Maidan.

March 3 (Monday at Maidan)

|

"'Ukraine' means 'land on the edge,'" or so Lonely Planet declares. It's a convenient definition, given current events, but "the borderland" might be a more accurate translation (though even much that is under dispute). It's interesting how names reflect identities, with some peoples and countries, most famously China, having names like "the middle," reflecting self-centeredness. Both "border" and "middle" would apply to Ukraine, wedged between Orthodox Russia and Catholic Eastern Europe, plus — at times — Islamic Turkish empires. It is no coincidence that a critical episode in fighting Russian expansionism was a conflict in Crimea, and that it was the flashpoint for Russian expansionism as I arrived in Ukraine.

The Maidan, also known as Independence Square, is the center square of Kyiv, and was thus the epicenter of both the Orange Revolution in 2004 and the Euromaidan protests of the past few months. For those who don't recall or want to look it up, in the Orange Revolution, Yanukovych — Russia's man in Kyiv — won an election under shady circumstances, from those of the vote itself to the poisoning of his opponent, which ultimately deformed his face rather than killing him. After protests, the election was rerun and Yanukovych lost.

In the decade since, though, Yanukovych came back while the opposition fractured. It took another Maidan-based revolution to get him out for good. This time, the spark wasn't a fixed election but Yanukovych reneging on signing a European Union trade deal in order to get a $15 billion loan from Russia. Though Ukraine's perilous economic state meant there was some sense to this move, many (a) blamed Yanukovych's corruption and graft for this economic state and (b) believed that he took the deal because it would allow the corruption and graft to continue unabated. Thus Euromaidan was born.

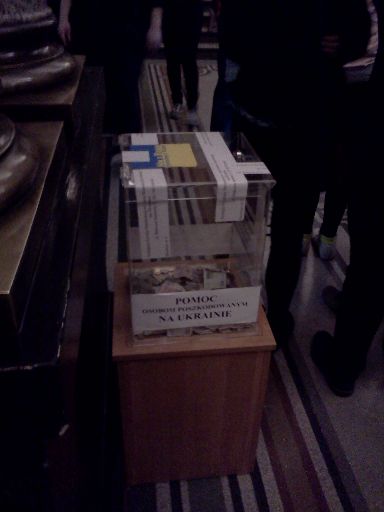

The State Department warned Americans against going there. Last month, with snipers shooting to kill, this was for good reason. In March they ascribed the warning to "crimes of opportunity." State Department warning or not, this was the first place Mila took me to on my first morning. Fog was thick and the smell of burning wood — and occasionally burning plastic — was in the air, as protesters chopped firewood to use as fuel to keep warm. Simple food was provided to protesters as sustenance, and tents occupied the square as well as the main street for blocks each way. Anderson Cooper would later call this atmosphere "like something out of WWII," but, though it might have seemed like a war camp, it lacked the inevitability of war, and was in the midst of the tall buildings of downtown Kyiv, which were still used for their day-to-day functions.

We walked around the area, seeing tents, protesters, and most of all memorials — pictures, candles, and flowers everywhere, even on the numbers of a large clock by Instytutska Street, now infamous as the place where government snipers, thought to be part of the now-exiled Berkut police unit, killed dozens. It was there that I saw the first of the makeshift barricades that kept out cars (and larger vehicles like, say, tanks). They protected the demonstration from all sides, and were made up of all sorts of detritus one could imagine: Bricks from now-partially bare sidewalks, metal gates, wood, tires, and so forth. I had noticed, a mile or two away, that some benches lacked metal slats, and wondered if those were now at Maidan (or even consumed in either the heating or violence-related fires there). Perhaps people picked up these "supplies" on the way to the square from their homes? This protest was not strictly in the Gandhi/MLK mold, so "borrowing" some supplies was not beyond question. Neither were Molotov cocktails — used, they say, only defensively — but that was last month. This month was a combination rally, celebration, and memorial.

|

|

|

Seeing the square in person gave me an appreciation of the magnitude of the fires we all saw videos of during February's conflict. While most of these fires were set to keep snipers from killing people, an earlier fire, most likely set by government forces, had engulfed the huge Trade Unions Building, which housed much of the logistical team for Euromaidan. One of the dead was found in the burnt-out building, which now stands with the memorials as a testament to what happened there. Outside of it is a partly burned billboard banner for Ulysse Nardin luxury watches.

|

|

Having gotten most of my news from the radio and Internet, I also missed this novel flag — consisting of Ukraine's coat of arms superimposed on the EU flag. I now have a knit cap emblazed with this combined emblem (which became more practical than my bulky cap when weather started to warm as the month progressed).

|

Maidan, being central, is near a number of restaurants, including one of Mila's favorites, Zdoroven'ki Buly, which, not being a terribly catchy name, I am just going to refer to as "Z.B." or "the restaurant near Maidan." Mila was helpful in pointing out the vegetarian items, so I had salad and cheese dumplings — "varenyky" to Ukrainians, "pierogi" to Polish-centric Americans. The salad bar had a small bowl each patron could fill with whatever he or she wanted — from seaweed salad to more traditional cabbage, beets, and carrots. I went for both variety and volume. I also grabbed a ring-shaped piece of bread, a bublik, similar to a staple of Istanbul street food, the simit. (Appropriately enough, my last trip overseas had been to Istanbul, which is also a handy reference point for people who don't know where Kyiv is; it's half-way between St. Petersburg and Istanbul.) To drink I had compote, the dried-fruit juice quite common in Ukraine. I also had tiramisu for dessert. It was very good, especially since I didn't have high hopes as a vegetarian in the former Soviet Union. The décor of the cafeteria-style restaurant included cashiers in traditional outfits and sections with world themes — China, ancient Egypt, etc. The latter seems a popular design element; we'd later go to a mall with similar themes.

All told, it was only $7... for both of us. This seemed to be the pattern for the next few meals — though eventually we got up to as much as $10. Ukraine's average income is less than a tenth of America's, so things are priced accordingly. My SIM card — with unlimited calls, texts, and Internet — was only slightly above $6, and I didn't even use half my time by the time I left. The subway was 20 cents, pretty good considering that the three lines have a total length of over 40 miles. Museums never seemed more than $5. Grocery items are about a quarter of the price you might expect. Rent isn't that much either. When I arrived, the native hryvnia currency was at ten to a dollar. But while I as an American divide the prices by ten, for a native Ukrainian — in terms of income — it's about the same as dollars, so that $7 dinner for two is, effectively, like a $70 dinner for two, which suddenly doesn't seem so cheap considering the casual dining experience. Then again, incomes in Kyiv are far higher than those in the countryside; judging from the per-capita gross city product, three is, roughly speaking, a good number to divide by — or multiply by — here.

For me, though, it's cheap. Coffee seems to be an exception to the rule, but I guess cafés always have to charge enough to stay in business, and if Starbucks can charge $4, Kyiv coffee houses can get away with 20 hryvnia. Oddly, it seems like it can be expensive for tourists insisting on the best accommodation; MSN ranks it as one of the ten most expensive cities in the world on this basis. Overall, such a price structure reminds me a bit of Hong Kong, which is also inexpensive for purposes other than hotel stays. Downscale lodging is available, though; on the Kyiv subway I did notice ads for $20 hotel rooms.

Though it may sound surprising, Ukraine has one of the most equitable distributions of income in the world, on par with the countries of Western Europe. Nonetheless, the country also has more than its share of billionaires, likely one fact that fuels the protests, not just because of frustration about graft, but because activists who get a billionaire on their side won't lack for funding. Unfortunately, this also fuels fringe anti-Semitism, since far right leaders seem to assume that all the billionaires are Jewish, or at least partly so:

When asked if all Ukrainian oligarchs are actually Jewish, [Ukrainian Right Sector leader Igor Mazur] shrugs. When asked if Yulia Tymoshenko, one time Ukrainian prime minister and an oil and gas oligarch is Jewish, he says only, "We don't know for sure. We think she has some Jewish blood in her."

He doesn't think he's anti-Semitic — citing the half-Jewishness of his son's godfather, and claims that 1% of his base is Jewish, this in a country where somewhere between 0.1% and 0.5% of the population is Jewish. Fortunately, that base has only about 5,000 people, and none actually in government. Nonetheless, Russian President Vladimir Putin says they're in charge, and, shamefully, some in the West believe him. Aside from the "some of my best friends are Jewish" argument, the group has done other things to try to eschew their anti-Semitic image, such as meeting with Israeli authorities and honoring a Jewish protestor killed in Maidan, but the aforementioned statement and their willingness to use violence to oppose the Kremlin aren't helping them.

On the Maidan and in the restaurant, Mila told me a few things that I hadn't heard from the news. Apparently, folks in Kyiv believe that an ad hoc catapult was the motivating factor for the president to flee. It sounds far-fetched, but I hadn't even heard of the catapult, reported here, cartoonishly illustrated by Taiwan-based TomoNews, and, much later, related in a Cracked article that tells the story of the protests from an insider's view. Mila said the person who built the catapult became a folk hero, well known to Kyivans.

Posters abounded, many with recently released political prisoner and former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko. I saw fewer and fewer of these as the days wore on. Though her unjust imprisonment was a cause célèbre — one of the main motivations behind the protest — her possibly shady business dealings have made her untenable as a leader in the eyes of many protesters and their supporters. Still, by the end of March, Tymoshenko would formally enter the presidential race. Mistrust of politicians is why the protest camp still persisted after Yanukovych's ouster.

Another poster has picture of Putin and a traditional farewell, which Google translates as "Godspeed on." This farewell was chosen due to its second word, which consists of the first four letters of Putin's name; it's a pun.

Mila also said that one of her students supported Russia's actions. No one was quite sure how to respond to such an opinion, so they just left it alone.

So avoiding the Maidan didn't happen. It would be possible but unnatural to do so anyway. Many of the city's attractions are nearby, and all three subways lines pass close by. Even if one were to avoid the square, though, one would still see memorials throughout the city. There is a sense in which, what 9/11 was to New York City, February's massacres were to Kyiv. There are posters all around, serving as memorials of those who, in many cases, we once only known to be missing. There was the shock that something like that could happen in a city like this. There was around-the-clock coverage, with new revelations each day, and uncertainty about what would come next. And there was an up-swelling of patriotism, as cars and children waived blue-and-yellow Ukrainian flags and backpacks and coats sported blue-and-yellow ribbons. It's hard not to be inspired by all that, even with the grave realities of what led to it and what might lie ahead.

|

Now, at first glance, Ukraine's blue-and-yellow flag appears to be the most boring national flag that bothers to be original. (Next-door neighbor Poland also has a two-band flag, but shares the red-and-white design with Monaco and Indonesia. Monaco's flag has been official for longer, though Poland had long used red and white to represent the country.) In fact, the flag symbolizes the clear blue sky over yellow wheat field, and is thus more resonant than most other countries' flags, which have only abstract meanings at best, such as red for courage or white for purity. Add to this the fact that it originated during the Europe-wide (attempted) Revolutions of 1848, and you've got a pretty good nationalist flag.

|

There is, however, an alternative flag, also waived at the Maidan, which is even more aggressively nationalistic. On it, the blue is replaced with red and the yellow with black. This flag has its roots in the WWII-era Ukrainian nationalist paramilitary that engaged in a series of guerrilla conflicts against Germany, the USSR, Czechoslovakia, and Poland, both underground Poland and Communist Poland. In this case, the representation and color scheme are stark, rather than bright, representing "Ukrainian red blood spilled on Ukrainian black earth." The association with a group which fought the communists during WWII aides Moscow's portrayal of Maidan as a fascist movement, sadly, rather than simply a nationalist one. It also doesn't help that the Right Sector uses a modified form of the flag.

Heading back, away from the smells of the burning wood, I was reminded of those two other very European smells: cigarette smoke and, on the subway, body odor. There's a reason declining to use deodorant is viewed as a European thing.

March 4 (Tuesday at 20th-century museums and monuments)

I'm not very good with jet lag. It's why I don't like short trips to Europe or Asia. So something low-key was best for this day. And I was glad to have help getting my phone to work, since putting minutes on my SIM card took four tries in four places before it finally took. The connection was 2G, and the connectivity was a little questionable after momentarily losing it, e.g., in the subway. But, in spite of all that, it was very useful to have the Internet at my fingertips in a foreign land (and, as I explained prior, fairly cheap, too).

I took the Metro to Arsenalna station; though the adjacent Dnipro station stands above the Dnieper, the height of the nearby slope means that Arsenalna might be the deepest Metro station in the world, depending on whom you believe. (North Korea has competing but unverified claims.) South of the city center, this is the station for several attractions, including a park containing memorials to Ukraine's greatest 20th-century tragedies. The war memorial, the northernmost of many in the area, has the Monument of Eternal Glory, marking their tomb of the unknown soldier, who died in WWII. Like those in other countries, this has an eternal flame, though this day it was barely visible in the fog. In addition to the unknown soldier are 34 named soldiers, whose tombstones lead up to the main monument.

|

Nearby is the Holodomor memorial and museum. The Holodomor was the mass-starvation of the Ukrainian SSR implemented by Stalin in 1932-1933. Ukrainian products were imported to Western Europe to fund the Soviet system, while the resistance and nationalism was crushed at home by not allowing food to enter. Figures aren't certain, but most estimates are that between two and ten million people died, the most-cited estimate being near four million. Cannibalism and eating leaves and weeds were rampant. An exhibition room lies under the memorial, with many details in English, though it's hard to pick out an exact narrative, since there's much about this mass starvation which still remains unknown. Also scattered throughout the room were photos from Euromaidan. It's not hard to make the connection here, both being examples of Moscow trying to control Ukraine via indiscriminate killing, with some level of obfuscation and plausible deniability.

I assumed that this uncertainty and deniability explained why the small, free exhibit, though chronological, was nevertheless not what I'd call "narrative"; it was somewhat difficult to follow what followed what and why. I later found that this was a feature of all Kyiv museums — long on detail, short on narrative.

From there I walked past the Lavra — the thousand-year-old religious complex — and to the war museum complex. There sat tanks, planes, anti-aircraft weaponry, and all sorts of other equipment used by Ukrainian SSR in Soviet wars. Most of these were in a small, outdoor annex to the main path, a path on which one could hear Soviet military music through speakers on each side. A tunnel of Soviet sculpture led to the WWII museum — the Museum of the Great Patriotic War — which was housed under a huge statue, the Motherland Monument. It was large enough to be visible throughout much of Kyiv, but, due to the fog, there were times at which I couldn't see even its head while right in front of it.

|

The museum itself had myriad artifacts and each room had a description in multiple languages of what was contained therein. If you knew Russian or Ukrainian, you could spend a whole day there looking at everything. With the data connection on my phone, I occasionally but slowly looked up what some things meant, such as the Soviet propaganda poster saying, "Fascism — that's war." And though I mostly refrained from doing that until I exited, even I, with my meager knowledge of Cyrillic and German, took longer than I might have expected, and was surprised to hear an announcement that the museum was closing, this when I hadn't yet finished the ground floor. I expected to be ushered out, but, thankfully, I was merely pointed to the upper floors; it seems they're less strict about closing time than their Western European counterparts. By the end, though, either jet lag or a day spent trying to read Cyrillic — or some combination thereof — had given me a huge headache.

Because by now I was far from any Metro station, I decided to walk down to and across the Dnieper. At first I was worried that there was no pedestrian walkway, but there was, a sidewalk between the oncoming traffic and the Soviet-era metalwork railing. The long bridge gave me time to notice license plates, and I noticed that they used only numbers and letters common to both Cyrillic and Latin alphabets. No "N"s or backwards "N"s. After crossing, I stopped at my first Ukrainian supermarket to get some things for Mila and myself. Mila later told me I'd gone to the "expensive" supermarket — its name actually translates to "banquet center" — though of course it wasn't expensive to me.

March 5 (Wednesday up St. Andrew's Descent)

Wednesday Mila showed me around the lower part of the town, the part nearer to river level, called "Podil," literally "lower part." She lives near the river, too, but on the other side from all things touristy, on Rusanivka, a small "island" formed by what seemed like a canal ringing it on three sides, the river being the fourth. It was mostly a mix of high-rise and green space, with most roads being more like alleys. Still, it has restaurants and supermarkets, as well as little booths and tables selling everything from bread to phone cards and from produce to lottery tickets. A tiny church is located just across from the pedestrian bridge I'd use once or twice a day. The island even has its own "well," though Mila told me that (a) it doesn't actually look like a pre-modern well and (b) it is easier just to buy water from the store, which is what she does. Kyiv's tap water is not safe to drink.

|

We wandered around Podil until we got to the Chernobyl museum, which, like the others, was rich was artifacts but a little short on description. Mila nonetheless remarked on how well done it was, and, I had to agree that the exhibits were impressive. And, in spite of my complaints about narrative, the exhibit did make it clear that the USSR kept too tight a lid on information, news of the accident only coming out when Western countries raised alarm about the amount of radioactive material being detected. We'll never know how many people died needlessly due to Moscow's refusal to allow free flow of information. The museum drew parallels with the victims of nuclear weapons in Japan, and, though I didn't see it stated there, I've heard allegations that Chernobyl was designed primarily to produce weapons-grade plutonium, with power production a byproduct. Downstairs from the main exhibit was a large display about the Fukushima disaster, with all its parallels to the far worse disaster at Chernobyl.

After this, Mila took me to one of the restaurants of the restaurant chain Varenicnaya Katysha. This was more of a traditional restaurant, but with décor — including books and artwork — based on what one would find in a Ukrainian home. Their Facebook page gives a taste of the nostalgia, if not the food. One dish we had was a bread-like dumpling stuffed with potatoes, and the other was cabbage, also stuffed. Again quite good and again, even with a latte — a habit Mila picked up in Kyiv — quite cheap.

This was the day on which NATO made a statement about the Crimean crisis, and a few hours before the statement, a woman I bought something from commented — in Russian, which Mila understands — that she heard a rumor that Ukraine would join NATO. I wondered whether that inspired cheer or fear — after all, she was speaking Russian — and Mila told me that it sounded like the former. That contrasts with what Mila's Russian grandparents had been hearing — either through the rumor mill or through Russian media — that people get shot here just for speaking Russian in public. (This turned out to a grim foreshadowing of the effectiveness of Russian propaganda on Russian relatives of Ukrainian residents during the Donbas and 2022 wars.) I'd guess most people, even Ukrainian-speakers, do in fact speak Russian in public now and again; ads and other public displays are often in Russian (though more often in Ukrainian). The menu of the restaurant was also in Russian &mash; only Russian &mash; as were the placemats. There was a bit of another language on the menus, but that language was English. (If you read neither language, there were also pictures of the food.) The students in Mila's English class, when not speaking English to each other, speak Russian, not Ukrainian. It's a bit reminiscent of Montreal, in that official signs are all in one of the widely spoken languages, but people and businesses are just as comfortable dealing with the other. Yet Russian media were telling those in urbane St. Petersburg that this is what's happening in Kyiv. Imagine what they heard in occupied Crimea on the run-up to an anti-Ukrainian plebiscite.

Rumors here have been rampant for some time. In October 2013, Mila wrote me, saying that her students were talking about the U.S. dollar buying half as many hryvnia as before. The rumor was that confidence in the dollar due to the debt ceiling crisis would cause either the dollar to be devalued by two or the Ukrainian currency to be revalued by two. That's clearly against the trend, but understandable give the low cost of living here and past experience with currency instability. She wondered if it might be best to keep the money she earned in the local currency. I wrote back, "This is not a currency to trust over the dollar." By the time I visited, it was worth less than ever — sliding about 20% — and she couldn't convert what she'd kept, due to new limits on transfers abroad. As this article points out, that's only more likely to cause a black market in which the currency is worth far less.

The strange thing is that currency traders are both buying and selling hryvnia for prices above the market rate, selling hryvnia for as little as seven to a dollar and always buying below the market rate of ten. This seemed at odds with reality; wouldn't the locals just show up and trade their money for dollars? But, of course, if there are currency exchange limits, there will be even stricter regulations at tourist money exchange spots. Apparently, in order to get your dollars back, you need to show them the receipt you used to buy your hryvnia in the first place.

After lunch, we went up the road used most commonly for going from Podil to the historic upper city, Andriyivskyy (St. Andrew's) Descent. Mila told me there were some of the most expensive homes nearby — many still unsold — and that there were usually many merchants selling various items along the street. Due to it being a weekday, however, we only started seeing them as we neared the top. A few days later — on a weekend with better weather — the merchants went all the way to the bottom of the hill. Due to the fog, the views walking up weren't what they'll be a few days later, but it was still an essential Kyiv experience, and I did indeed wind up buying souvenirs on the way up.

Near the top is a smaller one of Kyiv's historic churches, St. Andrew's, and, just past the top, is one of the largest, St. Sophia's, supposedly named after the even-older Hagia Sofia in Istanbul. A statue of hetman (military commander) Bohdan Khmelnytsky is in front of it. He liberated Kyiv (and much of modern-day Ukraine) from Polish rule in the 17th century, but left it under the protection of the Russian Empire to legitimize the separation from the Poles. The Russian Empire viewed this less as a protectorate than an acquisition. The original statue dates from 1888, and the Tsarist leadership convinced its sculptor not to show the heads of the vanquished — a Pole, a Jew, and a Catholic priest — under the hooves of Khmelnytsky's horse. Khmelnytsky's forces killed half the Jews in the land he conquered.

The less offensive version allowed Russia to use the monument (and Khmelnytsky's memory) to demonstrate the strong ties between Russia and Ukraine, though obviously Ukrainian nationalists have a different interpretation of these historical events; many view Khmelnytsky as a symbol of Ukrainian nationalism. To that end, on the base of the state is a plaque regarding Yanukovych's challenger in the Orange Revolution, then-President-elect Viktor Yushchenko. It reads (in Ukrainian), "At this point, January 22, 2005, the free voice of the Great Council of the Ukrainian Cossacks chose, swore in, and ordained a hetman, Ukraine national President Viktor Yushchenko. Glory to Ukraine!" That seemed a bit confusing, especially because Yushchenko wasn't sworn in until the next day. But I later found that, the day prior to his inauguration, he took part in a ceremony pledging allegiance to the Cossack brotherhood and Ukraine. This traditional (or pseudo-traditional) ceremony was clearly meant as a symbol of Ukrainian nationalism, and thus opposition to fealty to Moscow. And, indeed, the phrase "Glory to Ukraine" is a slogan seen all throughout Euromaidan, including over its main stage.

The cathedral complex itself is large and historic, and the cathedral itself is chock full of 11th century frescos and mosaics. There was a lot to see, although unfortunately continued restoration worked blocked much of the view. There were also exhibit halls upstairs, with newer works, replicas, and similarly old works from a nearby historic church destroyed by the Soviets. There are plans for reconstruction, though I'm not sure what phase they're now at. Upon exiting the complex, I noticed yet another collection of hundreds of flowers and candles, with photos of and writings about those murdered in Euromaidan. You can leave Maidan, but you can never get far from what happened there. I would later see a similar display in front of a Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Wrocław, Poland, hundreds of miles from Ukraine.

We then walked to the Golden Gate; unlike in San Francisco, this is an actual (if reconstructed) gate to the city, not a body of water. (Both are, however, named after similar entities in Istanbul.) There is a subway station right next to it.

March 6 (Thursday at Mila's favorite places)

Mila wanted to take me to her favorite park, Peizazhna Alley (more photos here and here, and history here). This turned out to be only a few steps away from where we'd been the day before, looking for views just off of Andriyivskyy Descent. This park is full of three-dimensional mosaics for kids to play on, serving as benches, jungle gyms, and so forth. One particularly large and creative one was based upon Alice in Wonderland. Other three-dimensional art was nearby, both for children and for adults (traditional statues).

(Side note: In the years since I first wrote this, public art — especially murals — has spread throughout the city, this site having a few good examples.)

We then went into the Lviv Chocolate Factory for hot drinks and truffles. I had hot chocolate, while she, as usual, had latte. I'd buy some truffles on a later day, but I'm afraid they weren't really set up to be transported, so I ate them before returning to the States. I waited for a later day because the place was mobbed with people buying chocolate for International Women's Day, which there stands in place of both Mother's Day and St. Valentine's Day. Curiously, though, most of the people buying chocolates — and seen transporting flowers on subsequent days — were women themselves.

We then walked through other highly trafficked areas of Kyiv, including past the Roshen brand chocolate store. More on it, and its significance, later. Across the street from the Roshen store is the Pinchuk Art Centre, which shows various exhibitions. When I was there, the main exhibit regarded colonialism in the Congo region with pictorial assemblages made of colorful beetle carcasses. I don't regret seeing them, but I wasn't tempted to take one home.

For lunch, we went again to Z.B., the restaurant in the Maidan area, walking up the main approach, so I got to see where the open road ended and the tents began. This time my dumplings had potato rather than cheese, the salad bar had a slightly different selection, and I had a light pastry, which Mila insisted wasn't sweet, but which seemed sweet enough to me. I also had grape juice; due to a mistranslation, I thought it might have been pomegranate. When you know hardly any of the language, sometimes you guess wrong.

After she went back to teach, I walked around the Euromaidan area a bit more, seeing more of both the outskirts and the central Independence Square (Maidan). One of the things I saw was a person nonchalantly walking by in a zebra costume. This was not the first person in animal costume I'd seen around town. I wasn't sure if it was a promotion, or entertainment, or a scam of some sort. They generally congregated in similar areas as the "dove men," men who carried fancy, white doves, though I was never clear on whether they were trying to sell them, have them pose, or something else. I only know that the one English-language "review" for Lovers' Bridge voted it a "one" because of "2 guys ... who will put Doves on you and then expect you to pay 100ua without giving you a chance to decline." So I avoided them all.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

From there, I walked to St. Volodymir's Cathedral, the inside of which is a seamless mix of classical and art nouveau, the latter including stained glass, much of the entryway, the bordering and edge patterns, and even some frescos. It is in the museum district, which is centered around Taras Shevchenko Park, the greenery of which contrasts with a maroon-red university building.

The nearby Metro station, Universytet, apparently has one of the world's longest escalators, at 87 meters. (The deeper Arsenalna instead has a series of two long escalators.) I went down and then took the subway to the Babyn Yar memorial, at the ravine where the Nazis killed thousands of Jews, and subsequently others, in arguably the first wholesale massacre of the Holocaust. I should actually say "memorials," since both north and south of the subway stop are multiple memorials. First I saw one to the children killed there, just to the station's northwest. This was quite near where the massacre occurred, but my guidebook told me to look for a menorah. I found an addition plaque with a menorah in the ravine itself, but that wasn't what the guidebook meant. Southeast of the station was a cross (for Ukrainian nationalists killed there), and, further to the south, the massive Soviet memorial statue, with no mention having been made, of course, of the religion of those first massacred there. Finally, I found a list of memorials with GPS coordinates and was able to find the Jewish memorial, a menorah well to the east of the station. I wonder how many people have tried to pay tribute to the victims of the tragedy, only to be foiled by the confusing geography. Directions relative to the station or the giant television tower — supposedly the tallest lattice tower in the world, though you wouldn't know it through the fog — would have helped greatly here. In the end, though, I saw them all, albeit getting back later than expected.

March 7 (Friday looking at Folk Architecture)

The fog finally lifted Friday, making for a bright and beautiful day. Mila and I caught a marshrutky, a shuttle-sized privately run mini-bus with an allegedly well-defined schedule. Sometimes packed beyond comprehension, and sometimes more reasonable, this is, in some sense, the final link (before walking) to places not served by larger (and faster) means of transport.

In the bus, newcomers in the back would give me the fare, which I'd then walk up to the driver. Once off the bus, Mila told me that I wasn't expected to walk back and forth, but could have just handed the money to the person in front of me; sometimes the driver would even hand back change the same way. It struck me as a stark contrast with two images of that part of the world: One was the large-scale corruption which made leaders into billionaires while bankrupting the country, or so those supporting the protests allege. (They back up these allegations with math, noting that if you divide the amount alleged stolen by the number of years Yanukovych was in power, it more than makes up for the annual shortfall which the country needed some sort of relief from.) The other form of theft countries like Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia are known for is cyber-theft. So when it comes to stealing billions from the masses, there isn't much trust there, but on a marshrutky there's far more trust than you'd see in any American city.

Our destination was the Open-Air Museum of Folk Architecture and Rural Life, on which was built over a hundred buildings designed in the style of Ukrainian rural homes, churches, etc. Subdivided into regional "villages," it gave a detailed, life-sized view of Ukrainian folk architecture (including, in the case of the last "village," that of the Soviet era). One could easily spend all day in such a place, and we basically did. Though it was a beautiful day, it was still a March weekday, so I think there were more dogs and cats than people. Still, a film crew seemed to be using the backdrop, and one older woman guided us through half a village. She asked whether Mila knew Ukrainian as well as Russian; since Mila didn't know Ukrainian well, the woman said she'd speak Russian. Mila later said it was actually more a mix of the two, going back and forth between the two languages, as folks in Kyiv tend to do. Mila posits that most folks aren't even conscious of which language they're speaking. And, again, like the museums, the "village" was exhaustive and detailed, but without much of narrative or explanation. You're not going to learn history, but it is a change of pace from the city, even with its many parks.

In one "village," the lake was solid ice, excepting the portion by the edge. I threw a rock to the ice, and there appeared no evidence of (liquid) water below. This prompted Mila to note that it could be quite cold in her apartment during the fall, then quite hot when the government turned on the heating system. I'm not sure about the logistics of that, though I'm pretty sure that's not how it works in the U.S. (However, I did once had an apartment with a very old heater, and the gas company would turn the pilot on and off, each once a year. This was appreciated since, not only did the burning pilot light use energy and add to warmth, it also blew out once. They probably should have updated the heaters there.)

I later found out that these artificial villages were about as far south from the city center as they were east from the historic village of Boyarka. This is the town on which author Sholom Aleichem based his turn-of-the-century stories. These stories were later turned into Fiddler on the Roof, the most well-known American portrayal of Eastern European rural folk life (and the play my high school put on when I was a senior; I was in the orchestra). People familiar with the play might be shocked to learn that the real-life Anatevka is a surburb of Kyiv, only an hour away from the city center via public transport.

For our late lunch (or early dinner), we went to another location of Varenicnaya Katysha, this one on the island upon which Mila lived. This one was, if anything, more homey, offering adults a nostalgic trip to the better side of Soviet life in Ukrainian SSR, and offering the kids a play area and a piano; older kids were free to (and did) play it. The best thing we had there was one of the simplest and most traditional, potatoes and onions (perhaps with some mushrooms if memory serves), pan-fried. Also simple and good was cauliflower in a cream and cheese sauce. Even for a vegetarian — no, especially for a vegetarian — Kyiv isn't the healthiest place to eat. The third entree — at these prices, why not? — was a pancake made of peas. Unsurprisingly, it wasn't the best thing on the menu. We finished the meal with poppy seed cake.

Most nights in Kyiv, I couldn't resist turning on CNN to see what the bigger picture was in Ukraine. This was how I learned that former Georgian President and Putin invadee Mikheil Saakashvili, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, and Russian oligarch-turned-political-prisoner-turned exile Mikhail Khodorkovsky had been on the Maidan stage during my stay there. One night I even saw a split screen between Maidan and the Stanford quad, a place I've spent much of my life, where a Stanford resident (probably from the Hoover Institution) was being interviewed. On this particular evening, I heard Russia claim it had to take Crimea because, "Moscow cannot ignore calls for help." I couldn't help but think those "calls for help" really originated from Moscow. Few nations are buying this shtick; the sad thing is that some individuals are. (A year later, Putin fessed up, but, years later, his apologists still believe the original story.)

March 8 (Saturday at Lavra, city parks, and malls)

On March 8, I read an editorial by former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, in which she wrote

"The notion that the United States could step back, lower its voice about democracy and human rights and let others lead assumed that the space we abandoned would be filled by democratic allies, friendly states and the amorphous 'norms of the international community.'"

There is something to that, but it struck me as a contrast to the one time I saw her speak in person, when she was transitioning from Stanford to the George W. Bush campaign, and spoke at a Stanford event. I noticed no mention of human rights in her speech and asked her about that. Her response seemed to pay mere lip service to the concept. Not that I should have expected differently. Perhaps her most famous speech, at least up to then, was actually given in Kyiv itself, back in 1991, by then-President George Herbert Walker Bush. This came to be disparaged as "the Chicken Kiev speech." In it, the Ukrainian desire for independence from the Soviet Union was cautioned against due to the potential for "suicidal nationalism based upon ethnic hatred." Voters felt differently, though: 92.3% of Ukrainian voters would go on to endorse their parliament's declaration of independence, including a majority of Crimean voters. But opposing Crimea's further secession now — just like opposing Ukrainian independence then — would be consistent with the realist desire for stability above all, whether or not this view was couched in the language of human rights.

After reading Rice's article, I quickly got up for an early start to my day. I again went by the unknown soldier and Holodomor memorials, the thick fog now replaced by bright sun. Across from the latter was graffiti expressing similar thoughts to Rice's, but much more succinctly, i.e., "FUCK PUTIN." However, instead of the second "U," there was a backwards "N"; clearly the person who did this had some familiarity with English, but did not realize that, unlike in Cyrillic, what looks like a "U" in handwriting is not a backwards "N" when printed. (This is one of many "false friends" one finds between the Cyrillic and Latin alphabets.)

On a later day, I would see a somewhat similar mistake in a nearby museum: An English explanation with the very non-English "word," "dйcor" rather than "décor." In both cases, they're an "e" sound with a diacritic, so I could see the thinking, even though the Ukrainian for "décor" is a more straight-forward transliteration.

The museum I saw this at was at the huge Pechersk Lavra (Cave Monastery) religious complex, founded in 1051 and arguably the primary tourist and religious attraction of Ukraine. It is large enough that it is difficult to do it justice in one day; I'd try my best this day, but have to see other things — like "dйcor" — on another. Its structures are built on the hill leading down to the river, so many of them are visible in much of Kyiv.

Here my lack of ability in Ukrainian and Russian was the most evident, but also rather amusing. Two or three times I asked someone whether or not they spoke English, and the conversation turned out consisting of a mix of German and English, almost as though they didn't realize they were speaking two different languages, just whatever words were, to them, "not Russian or Ukrainian." Good thing I knew some German, and tried to use words I thought they'd know.

When I got there, it was around the opening hour, but for some reason there was no one to take either my entrance fee (about 30 cents) or my fee for the exhibits. Nonetheless, I walked around a bit, looking at the beautiful and historic (though mostly reconstructed) buildings — and views of not only the complex, but of the city and the river. However, not only wasn't it clear what I needed a ticket for, it also wasn't clear what was open. For example, after seeing that the Ukrainian Folk Decorative Art Museum's front door was locked, I asked at the Lavra entryway about that, and the person insisted it was open. I went back, and I still couldn't find an open entrance. Similarly, there was no entry to the main hall of the ornate Cathedral of the Dormition (just the side); to the Refectory Church, closed for renovation (though the ajar door allowed a bit of a peek); or to the Kyiv landmark, the Great Lavra Belltower (just plain closed, as, I'd find out later, was the Church of the Saviour at Berestove). These were, however, impressive from the outside and, making my way beyond them, I went to the caves themselves.

|

Originally designed for shelter, the caves eventually served as catacombs for the monks, though the exact location and construction of the caves has not remained the same through centuries of renovation, expansion, and reconstruction. If you believe the tales of 16th- and 17th-century travelers, they used to extend for hundreds of miles, all the way to Moscow and Novogorod. Currently — and, I'm told, historically — there are two cave systems, the "Near Caves" and the "Far Caves." They weren't easy to find without a guide — the Lavra complex is, well, complex — but I eventually made my way to and through each of them.

Before entering the caves, you must buy a candle to light your way. Though not packed, the caves were surprisingly full given the time of day. They are also big; not hundreds of miles, but certainly enough to require a fair bit of time given the various pilgrims praying at and kissing each station. They even had a religious service going on in one of the tiny underground churches adjacent to the cave paths. All the decoration lacks description, let alone English explanation, but I later learned that the underground churches include 18th-century icons, among other historic items. Each body was wrapped well in a large, heavy, detailed burial cloth which could be seen through the glass-topped coffin. (Allegedly, in Soviet times, there was no such cloth, leading to their being termed "mummies.") For those who don't have a good handle on Ukrainian Orthodox customs, belief, or history, this could get a bit repetitive after a while, but I spent time trying to figure out what I could — trying to decipher the names of the departed. I didn't know whether the partly unfamiliar old-style Cyrillic text was Russian, Ukraine, Church Slavonic, or something else.

After all that, I was hungry, so I stopped by one of the church cafeterias ("bakeries"), and, with some online searching, determined that they had a cabbage and onion coulibiac — a Russian savory pie — something perfect for snacking on while continuing to the next Lavra attraction.

After looking around a bit more, I proceeded to a sales cashier, asking about the micro-miniatures museum. She seemed not to understand what I was saying, and eventually gave me a $2.50 ticket to... something. That price was nowhere to be found on their price sheet, at least not for non-students, so I wasn't quite sure what she had given me. My best guess was that, because so many things were closed, the fee to see the main museums had been reduced. Either that or she assumed I was a student. But this wouldn't be the first time pricing would be confusing and/or flexible.

|

It turned out that paying for the micro-miniatures museum was only done at the entry to the museum itself. This collection of about 15 or 20 works of art over the last half century was housed in a single room, but could have, theoretically, been housed in a shot glass or maybe a thimble. Artwork sizes only went up to that of a cherry pit and features were far, far smaller than the width of a human hair. Mounted on the walls with magnifying glasses and minimal English-language descriptions, it was interesting and worthwhile. Perhaps more interesting was how they used the floor-space in the middle of the room: Therein was yet another exhibit on the Holodomor, the mass-starvation of Ukraine in the early 1930s. Included in this, for some reason, were letters in a 1939 correspondence between Hitler and Stalin; I don't read Russian, but I'm going to guess that neither of them came out looking good there.

After seeing the relatively small Gate Church and All Saints Church, most notable for their frescos, I went to the "Ukraine for the World" exhibit, housing a number of treasures and artifacts representing the ancient societies of what is now Ukraine. I then went to the comprehensive set of exhibits with artifacts from a thousand years of Lavra history. These were rather exhaustive, though towards the end, I noticed less and less English. By that point, though, this was almost a relief.

By the time I got to the museum of theater and musical instruments, I just about had my fill of museums for the day, so when they told me this one had an additional admission fee, albeit only $1.50, I started to leave. But they called after me that they'd just say I was a student and change me 70 cents, so I decided not to disappoint them. Inside, it seemed as though I was the only one in the museum, and I was led on a guided tour — albeit in Ukrainian or Russian — I didn't know which, though I think some German or English snuck in there too. In the theater portion of the museum, the playbills, posters, and photos told the story, so not much English was required.

My guide pointed out a theatrically related event that had occurred in Tiraspol. "Oh, in Moldova," I replied. "No, in Ukraine," she corrected. It turns out there is a good reason for this misunderstanding. Before WWII, Tiraspol was the capital of Ukrainian SSR's Moldavian ASSR. (ASSRs are one level below SSRs.) Moldavian SSR — later Moldova — was formed by combining parts of the Ukrainian region with parts of axis power Romania absorbed by the Soviet Union. (In this reorganization, Ukrainian SSR received the part of Romania that included the northernmost mouths of the Danube.)

This land exchange is relevant to today's Crimean crisis for two reasons. The first has to do with the notion that Crimea is rightly Russian either because it has a Russian majority or because it was part of Russia prior to 1954. In the latter case, we see that Moscow felt free to shift the borders of its SSRs (which is also how the German Königsberg region wound up as Russian Kaliningrad). Russia has as much claim to the Crimea as Ukraine does to Tiraspol, but you don't hear any agitation for the later. (If Tiraspol and other former Ukrainian lands were returned to Ukraine, it could theoretically solve a few problems, but more on that later.)

As for the population argument, that also returns us to WWII, when under the guise of being Nazi collaborators, the native Crimean Tatars were completely ethnically cleansed, with a high percentage dying in the process. Some eventually returned, but this marked the point at which Crimea's Russian minority became a Russian majority.

And that piece of Ukrainian SSR now a part of Moldova? Well, it turns out that its largely non-Moldovan population didn't want to be a part of the new state in 1990, and proclaimed a Pridnestrovian Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, the unrecognized state of Transnistria. Russia was decisive in the unrecognized state's war of independence and now has "peacekeepers" permanently stationed there. The state is arguably the last relic of the USSR, its authoritarian communist government remaining after all others had fallen, complete with flag and emblem with hammer and sickle, as well as endemic corruption far outpacing even that of its infamous neighbors. It is one of many unrecognized states Moscow uses to weaken its neighbors, the newest of which might be Crimea itself. Those who cite Russia as being far from Moldova or from Western Ukraine — thus having no pressure points on the population there — are forgetting the existence of this nuisance republic. The logical "solution" to this would be to apportion Moldova as before WWII, the majority-Slavic Transnistrian side reverting to Ukraine, and the other side going to Romania; Moldovan and Romanian cultures, ethnicities, and languages are virtual indistinguishable. Of course, the people and their leadership probably wouldn't go with this solution. Authoritarian states rarely yield power willingly, especially those with Moscow's backing.

As I walked out of the Lavra complex and passed the closed-for-renovation Church of the Saviour at Berestove, I knew I was overdue for lunch. To get back to the city center (or the nearest Metro station) required going traversing a street via a subterranean passage. These are more common in Eurasia than they are in the U.S., and, also unlike the U.S., there they usually have shops in them, for an efficient use of space. This one was complete with a food court, so I ordered a falafel wrap (tightly wrapped, so it looked deceptively small). The person asked whether I wanted "tea" as well, but the "tea" tasted more like fruit juice, so I'm guessing that was another mistranslation.

It hit the spot, though, so I was ready to keep walking, through the green space on the western side of the Dnieper. This led to the Presidential Palace, currently not in use due to refurbishing; I'd thought that this was unrelated to the political troubles, but later I heard that Maidan protesters marched on the Palace, so perhaps I was mistaken.

Also, across from the Palace was a pedestal that seemed to be missing a statue. I wondered if some folks hadn't decided to take down a representation — likely Soviet — of Moscow there. I know that many reading this will assume this was Lenin, but it wasn't Lenin. We'll get to him later. Long after these events, I found out that it was a monument to the "heroes" of the October Revolution, the one that swept the Communist Bolsheviks into power. I still haven't found a photo of what the statue looked like prior to the 2014 Revolution, though.

Walking further through the park, I came across a crowd gathered on a hazardously steep drop-off with one section of railing missing. Some folks were examining the drop-off and what was below more diligently than others, and at the top were teen boys on bicycles. They looked like they were preparing for a jump, though what they could land on that wouldn't hospitalize or kill them I have no idea. Every once in a while one would speed to the edge and trust his brakes to stop him a few inches short of disaster. It reminded me of the shocking statistic that Ukraine had the second-highest death rate in the world (per year per capita). First was South Africa (and that first-place distinction now seems suspect with their falling to #46 for the 2015 estimate, Ukraine retaining #2, with South-Africa-enclaved Lesotho jumping to #1). In Ukraine, much of the death seems due to "misadventure," though jumping off of cliffs is less common than the banal "adventure" of alcohol poisoning. The men are especially susceptible to such preventable deaths.

And these are a lot of people we're talking about. Ukraine is the largest country wholly contained within Europe, though Russia, Turkey, and Kazakhstan — each partly in Europe and partly in Asia — all have more square mileage. However, although Ukraine ranks in the top ten in terms of population, Russia holding the #1 spot, both of them are falling rapidly, even in comparison to countries that have some of the slowest population growth rates in the world. This is one reason why many Westerners see Russia's newfound aggressiveness as that of a nation in decline.

While the men in Ukraine (and, to a lesser extent, Russia) are known for dying, the Ukrainian women are known for their beauty. During the Cold War, this was certainly not the prevailing wisdom, our most common view of Eastern-bloc women being the steroid-popping Olympians. The idea that Ukrainian women were beautiful was, back then, good for a laugh line in a Beatles song. But today it's a different story. This is especially noticeable via the less subjective — but very relative — metric of thinness. Perhaps this, as with the high death rate, is related to cigarette usage, the sixth-highest in the world.

Whatever the reason, when Mila got here, she felt pressure to lose weight, even though she had just finished a weight-loss challenge, and wasn't overweight even before that. She claimed that she hadn't really lost weight since, but I thought differently the moment I saw her. During the course of my visit, she mentioned how — from pants to rings — things she brought with her were now too big. So clearly she had lost weight — later access to a scale confirmed it — and probably would not gain it back too soon.

After a while around the biking boys, though, it seemed like nothing was going to happen, and I moved on. The hundred-year-old, lock-laden Lovers' Bridge links the park I was in to the park adjacent to the city center, this over another extreme drop. After crossing it, I saw a statue of an elderly couple; apparently, the couple was a Ukrainian-Italian couple brought together in an Austrian war camp in 1943, and then ripped apart at the end of the war. They reunited six decades later — on TV. The poster telling this story encouraged couples to pose with the statue and share their photos via social media. This is not your father's war monument (and, to be fair, is barely a war monument at all).

Venturing further, there were horses for children to pet and a beautiful building that turned out to be a children's museum, with the antiseptic name, "Water Information Centre." A path then led down to the edge of the Maidan protest area, and I walked up to the one major central church I hadn't yet seen, St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery, reconstructed in the 1990 after being destroyed by the Soviets. The reconstruction was impressive and beautiful, and all the paraffin smoke from all the candles burning inside made the sun's rays rather striking against the art deco frescos inside.

Adjacent was a large Euromaidan memorial, and just outside was another series of flowers and candles, though I later learned that this was a monument for the Holodomor (which later that day I would see referred to as "the Communist inquisition"). Again, the parallel was difficult to avoid. Across the street was another small encampment, and, as I went to meet Mila for a late lunch / early dinner, Google Maps said the best walking route was right through the Maidan. I guess Google never got the memo from the State Department.

This being a weekend, the Maidan was busier than ever. I had a chance to have a really good look around the square itself, not just the surrounding areas. One thing I noticed was that one of the tables, where a woman was selling various historical books and knickknacks, had a box full of tiny red and green plastic swastikas.

|

This is... not something you'd see in the states, and I was left wondering what the appeal was. Were these supposed to be historical artifacts (accurate or anachronistic)? Were they supposed to appeal ironically, to those resenting Russian accusations of Ukrainian "fascism"? Or were they actually meant to appeal to a demand — real or imagined — from far-right elements of the Maidan. I must admit, I did see two swastikas spray-painted in Kyiv, though not in the Maidan, and I'd seen and would see similar numbers in cities to the west, including the next city I'd travel to, Krakow, Poland. So I'm not sure what to make of it, but it is a shame. Never mind their anti-Semitic implications; Putin apologists would have a field day with this one vendor's choice of merchandise. (In fact, my only other instance of seeing a swastika on the Maidan was one drawn on Putin's forehead, which has a pretty unquestionable interpretation.)

|

Putin, and the history of rule from Moscow in general, was a target of Euromaidan posters, in ways I've previously mentioned: An English-and-Ukrainian poster series calling the Holodomor "the Communist inquisition," the pun on Putin's name and "so long." And then there was a poster for today's International Women's Day. As far as I can tell, it had a Ukrainian housewife asking, "Who wanted the Crimean turnovers?" to a pleading Putin, who replies, "No beating today, lady, it's a holiday!"

Fittingly, 97 years prior, International Women's Day demonstrations sparked another February Revolution, the one that overturned the Russian Empire, leading to Russian democracy and Ukrainian independence — but only for a brief while.

|

The crowd in Maidan was big enough that folks had to funnel through to move, and the streets near the protest were busy with the usual weekend commerce, including women dressed up in Renaissance style clothing, selling sweets in front of the subway at which I met Mila. As this was near the Maidan, we went back to Z.B. I suppose no one can say I sampled a large variety of Ukrainian restaurants, but Mila knows her favorites and, better yet, knows what's vegetarian. I went for the salad bar again, got another compote, and then got an apple blintz; I wasn't hungry enough for the varenyky, and, besides, I'd had plenty already, both in restaurants and from the frozen food section of local supermarkets (though not, ironically enough, at Varenicnaya Katysha).

Also, I wanted to save some room for dessert. This was the day we finally went to the Roshen store, and I bought some candy for myself and for folks back home. Not as much as I would have had I had unlimited space in my suitcase, of course. They did have quite a selection, though, and, even at the company store, candy seemed about a quarter to a third of the price as the same product in California. They even had the candy box I'd often buy in the States — liqueur-filled chocolates — but for much, much less, only $1.50. There's a heavy markup on imported items it seems, at least candy. That works two ways, though; Mila told me that Lindt chocolates are triple the price in Kyiv as in the U.S., and you can't buy peanut butter candy at all. I brought nearly the legally maximum importable in Reese's Peanut Butter Cups for her students. Though Snickers, M&Ms, and others Mars products are prevalent there, there are still some things missing (and, I'm told, even Snickers doesn't taste the same there).

Candy actually plays on outside role in politics, since the Roshen baron, Petro Poroshenko, was a billionaire backer of the Euromaidan protests and the Orange Revolution before that. Paradoxically, he also helped found the party that brought Yanukovych to power, the Party of Regions, often called "pro-Russian." Poroshenko even served under him. In response to his Euromaidan political moves, Russia banned importation of the chocolates for "safety" reasons and seized and shuttered their Russian factory and warehouse. According to the linked Guardian article, among other sources, Poroshenko is the front-runner for May's presidential elections. (Note: Since I first wrote this, he has, indeed, become Ukraine's president, though he served only one term, the candy-maker ultimately being replaced by a comedian.)

After chocolate, we went to the nearby underground mall, this one as good as any above-ground mall. I bought several souvenirs: painted boxes, beads, a handmade mini-vase, and refrigerator magnets. The last two were bought at a booth that was uncharacteristically outside of the stores. In the Maidan, vendors were selling the magnets for $1 apiece, but here I could buy several at this price. Just after leaving, Mila told me that the vendor had said that this had been a slow day, and we were her first customers! Given the low price of the products, I wondered how that worked. Did she start late? Was it the nature of weekend shopping? Was it the infamously bad Ukrainian economy? Or did she pick a bad business and location? She seemed nice and had interesting items at good prices, so I hope she's able to hang on.

We capped off the day with a visit to a large supermarket, Novus, but all I recall from that were the sweets we bought: Ice cream, a rich pastry/cake, and more candy, both Ukrainian and international. Overall, it was a long day that, it seems, inspired more questions than answers about the state of Ukraine and Kyiv in 2014. Good thing I'm not a reporter.

March 9 (Sunday seeing what I'd skipped)

Since I hit the wall on museums the prior day, I still had some things left to visit in and near the Lavra complex. First was the Historical Treasures Museum, also called the "Jewelry Museum," since most of the treasures were jewelry and other precious metalwork. It was a big and comprehensive museum (of course), with much about the land's history, from pre-Roman to modern. As with many other museums, I found that, this Sunday morning, I was the only one there (aside guards, one in nearly every room); I was there for two hours and left around noon. Also, many items were given one-word explanations that I'd have to look up later, such as "torques," which are apparently ancient, stiff, metal necklaces designed for permanent wearing. (For some reason, though, they thought "quiver" needed more explanation.) Highlights included quality ancient jewelry pieces and a silver-and-coconut goblet, a motif I'd see again in other museums. The museum also had a Russian room (including Fabergé), a Western European room (with lots of beer steins), and a small room of Judaica, including some beautifully detailed sunflower-shaped spice boxes.

|

Sabbath prayers echoed from the time I entered the museum, which was right next to the Cathedral of the Dormition, to the time I left. They were coming from electric speakers discreetly placed in the façade of the church. My plan was more secular, though, so I left the complex, grabbed a potato-and-herb crepe from a kiosk, and went to the war museum area, passing by Soviet-era sculptures I'd previously missed, then returning to the War Relics Expositions.

Housed in a small building in the War museum complex and closed Tuesdays, the day of my first visit, the expositions number two. On the bottom floor is the "Foreign Wars" exposition, with artifacts from the military adventures of the Soviet Union. That's right: This was a memorial to the Cold War, told from the other side. With Soviet music in the background, I got to see all sorts of "relics" from the civil wars in Spain, China, Korea, Cuba, and Vietnam, as well as more obscure conflicts, like those in Angola, Yemen, and Ethiopia. Remember Ethiopia's infamous famine in the 1980s? When Western rock stars tried feed the hungry (with questionable results)? The Ethiopian government which led the country during the famine was hailed for its struggle for "proletariat internationalism" in a commendation at the museum, dated 1989. (The despot at the top has lived in Zimbabwe as an official guest of Robert Mugabe for over two decades, dodging a genocide conviction.) Other items touching on wider events included the use of the Olympic logo in 1980, and a Che icon plus he and the Castro brothers in photos and letters. They also had American medals from the Korean War. For a small room, it was packed full of history.

Outside the room was a list of conflicts Ukrainians (i.e., Soviets) had been involved in by the year the conflict began. Most noticeable was the final year, 1979, during which no less than eight Soviet-aided wars began. Afghanistan was just the tip of the iceberg.

Afghanistan was, however, a big deal, so upstairs, in the second of the two rooms, was a large exposition on the war, "Afghan tragedy and valor." Every type of weapon you could image — any type of war artifact in general — was there. There were mines and bazookas, tires and netting, letters and official papers, photos and sketches, watches and compasses, clothes and awards — both from the Soviets and from international organizations (e.g., for nursing). There were also 15 or 20 propaganda posters. Some of these had clear symbols of peace; it was unclear to me whether these called for peace through withdrawal or peace through victory. (Afghanistan, ultimately, would get neither of these.) Again, very different to see from the other side. Just outside of the war museum complex was a memorial with tons of flowers, dedicated to the "eternal memory courageous sons of Ukraine who fell in Afghanistan."

|

The trip back to the Metro took me down the park on the hill, and along the Dnieper, this on a beautiful clear day. There was someone fishing there, but most of the few people there were just walking. It also afforded a good view of the Lavra complex, at least if you squinted enough to ignore the nearby freeway.

|

I boarded the Metro at Dnipro, which was right next to not only the river, but an Azerbaijani restaurant; several former Soviet republics are culinarily represented in Kyiv. From there I went back to Podil, the bottom of Andriyivskyy Descent. After buying some chocolate truffles as the Lviv Chocolate Factory, I went to yet another small, dense museum, the famous Museum of One Street. This place told the story of Kyiv through Andriyivskyy Descent, with a few dozen displays, each having a short description regarding the relevant period and/or aspect of life there. There was also a temporary exhibition with historic photographs; one photograph in particular, which I'd bought a magnet of, seemed to be repeated two or three times, I suppose because it showed how empty that part of Kyiv had been in the 19th century.

|

I waited for Mila in a juice bar, ordering the unusual combination of pumpkin juice and olive oil, which tasted about the way it sounded (but not awful). Looking out, I was treated to the sight of a street guy in a Slayer hat pouring booze into a Sprite bottle. Some things, I guess, are almost universal.